Female genital mutilation is a chronic global problem. It demands a global response

(This article was originally published in euronews.)

In 2015, 193 countries committed to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which set out a “blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all” by 2030. Included within this was the aim to end the harmful practice of female genital mutilation (FGM).

As we stand at the dawn of a new decade, with just ten years left to transform the SDGs from a dream into a reality, it has become increasingly clear that the eradication of FGM will not be achieved unless there is a global response.

Target 5.3 of the SDGs requires every government to take action to “eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation.” Five years on from when governments pledged their commitment to the SDGs, many states are still not doing enough to protect women and girls from having their genitals cut.

According to research by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), if trends continue in the same direction and at the current pace, 68 million girls will have undergone or be at serious risk of FGM at some point during the 15 years between 2015 and 2030. Even more concerning is that this substantially underestimates the scale of the problem, because the figure only incorporates official representative data available from just 30 countries, 27 of which are in Africa.

When one country in Asia changed the global statistics on FGM

In UNICEF’s 2016 report, the global estimates for FGM prevalence jumped from the 125 million figure cited in 2015 up to 200 million. What happened? Were 75 million girls cut in just one year?

Put simply, no. A large portion of the increase was due to the addition of Indonesia in UNICEF’s estimates. New data was made available by Indonesia after the country’s Ministry of Health included questions on FGM prevalence in its 2013 household surveys. This was the first time Indonesia had requested this information and it revealed that a significant number of women and girls had undergone FGM.

What about the other 163 countries?

As part of achieving the SDGs, all 193 countries are duty-bound to measure the extent to which FGM occurs amongst their own populations. It is vital that information is both gathered and made publically available. Such data is invaluable in the effort to end this harmful practice because it pushes governments to take action, and provides a baseline from which we can measure the scale and effectiveness of interventions.

Although five years have already passed since governments have signed up to the SDGs, the Maldives is the only new country to meet the obligation by collecting nationally representative data on FGM.

When added to the 30 countries accounted for in UNICEFs figures, small-scale research studies and anecdotal evidence indicates that FGM is happening in over 90 countries across the globe, and on every continent except Antarctica.

Despite this mounting evidence base on the global pervasiveness of FGM, levels of awareness and acknowledgement amongst the public and government officials regarding the global nature of the practice remain low.

What would the global statistics look like if we were able to obtain reliable data on FGM prevalence for each of the 90-plus countries where we are aware that FGM is present?

FGM is global, but so is the movement to end it

6 February was designated by the United Nations as the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation. It provides a useful moment to reflect upon major developments in the fight to end FGM across the globe, and particularly in countries where it is not widely acknowledged but should be.

Although we are lagging behind in measuring the national prevalence of FGM, survivors, activists, and grassroots organisations across the world are breaking new frontiers in their fight to end the practice. They have been conducting small-scale research surveys to document what is happening at the grassroots level, providing support to affected women and girls, and successfully advocating to introduce and enforce legal bans with legislatures and before the courts.

International women’s rights organisation Equality Now has partnered with the End FGM European Network and the US Network to End FGM/C to produce a new report that will be released in March and will, for the first time, bring together available information about the practise and pervasiveness of FGM from over 60 countries that are not currently included in “official” data on FGM.

New studies documenting the practice of FGM/C (female genital mutilation or cutting) in Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia, and Malaysia have been published by activists and researchers in 2019. In addition, a nationally representative survey from the Maldives was published in December 2019, providing concrete and reliable evidence of the practice of FGM within the country.

In Oman, small-scale studies which demonstrated high prevalence of FGM, combined with local activism, prompted the government of Oman to pass a law banning FGM in October 2019. Oman is only the third nation in the Middle East – after Egypt and Kurdistan (part of Iraq) – to pass an anti-FGM law.

Female members of parliament from across party lines in New Zealand came together to pass a bill in November 2019 that closed loopholes in the existing anti-FGM law.

Meanwhile, in Australia, the High Court passed a landmark ruling in October 2019, overturning a previous decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal. The High Court held that cutting of the clitoral hood, or ‘khatna,’ as practised by the Bohra community is a form of FGM that was legally banned in Australia. This ruling underscores the need to end all forms of FGM, regardless of type or perceived severity of the practice.

In the United Kingdom, the first-ever successful prosecution for FGM took place in February 2019 under a 35-year-old anti-FGM law. Ireland also had its first conviction under anti-FGM laws in January 2020.

In contrast to these successful anti-FGM efforts, in the United States, the federal anti-FGM law has fallen into limbo after it was declared unconstitutional by a District Court in Michigan in 2018. In 2019, the US Department of Justice took the unprecedented step of refusing to defend the constitutionality of the federal law and did not appeal the decision of the District Court.

Though survivors and activists in the US were deeply disappointed by this decision, they banded together to advocate with members of Congress to pass an amended federal law on FGM. It is expected that the new bill titled “Strengthening Opposition to Female Genital Mutilation Act” will be introduced in Congress in 2020.

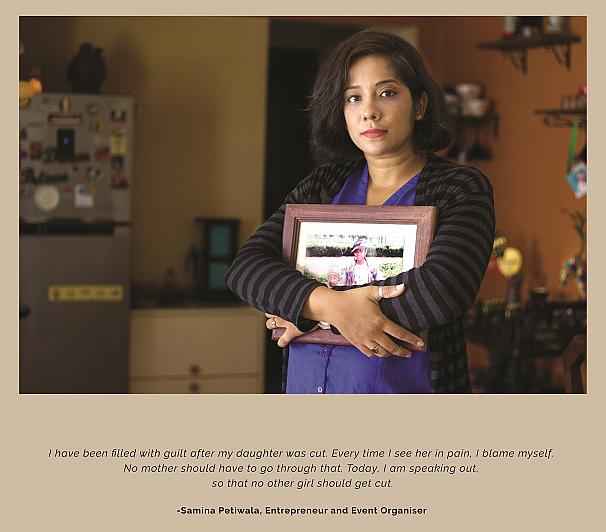

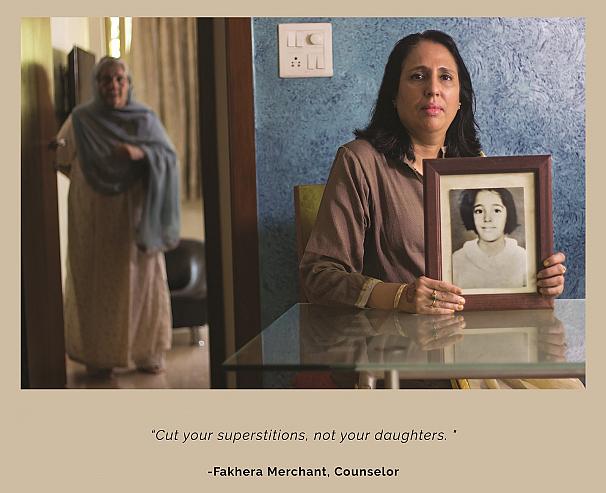

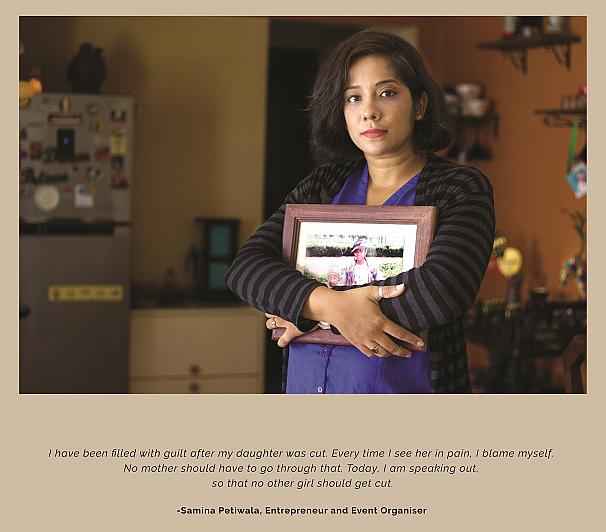

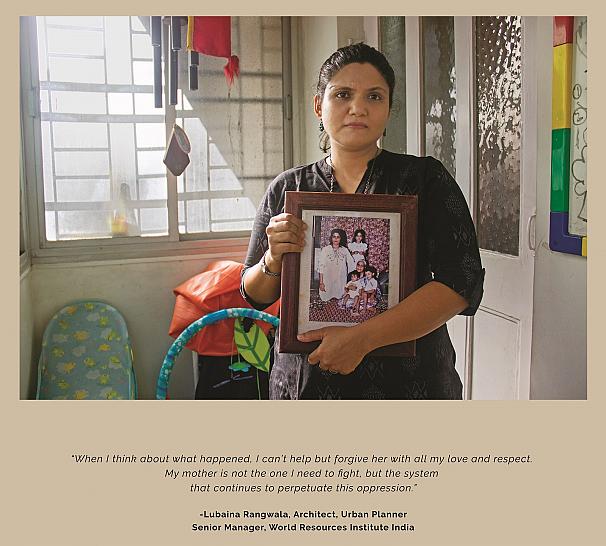

In India, non-governmental organisation Sahiyo launched its Faces for Change photo campaign in June 2019. The first such photo campaign in Asia, Faces for Change highlighted the practice of FGM through portraits and personal stories of eight FGM survivors from the Dawoodi Bohra community in India. Sahiyo and StoryCenter have also released ‘Voices to end FGM/C’ – a digital storytelling project which supports women and men impacted by this issue to tell their own stories, through their own perspectives, in their own words. Today, a series of 27 short videos addressing FGM created by survivors and advocates from countries and communities around the world will be released as part of this project.

Efforts to end FGM need to be accelerated

The Global Platform for Action to End FGM/C fosters collaboration among grassroots groups, civil society organisations, survivors, and activists around the world to accelerate action to end FGM.

The outcome of an FGM-focused pre-conference at Women Deliver 2019, the Global Platform for Action to End FGM/C unites voices around a Call to Action focused on five critical areas, which are as follows:

● Supporting change from within – challenging social and gender norms;

● Strengthening the evidence base through critical research;

● Improving well-being via support and services for survivors;

● Addressing emerging trends around FGM;

● Increasing resources to achieve the global goal.

By January 2020, more than 520 organizations and individuals around the world have endorsed this Global Call to Action.

With only ten years left to eradicate this widespread and harmful practice affecting millions of women and girls globally by 2030, the time to accelerate action is now.

FGM is a global practice which requires a global response. Political commitments must now be acted upon fully by accelerating and globalising efforts, collecting and circulating reliable data, and providing the proper funding and support to NGOs and local services needed to put in place effective policies and interventions to eradicate FGM once and for all.

- Divya Srinivasan is a human rights lawyer and South Asia specialist working with international women’s rights organization Equality Now.